This blogger has received official confirmation that the Statute Law (Miscellaneous Amendments) Bill, 2014 passed by the National Assembly on 13/08/2014, was assented to by the President of the Republic on 28/11/2014 thereby bringing the Copyright (Amendment) Act 2014 into force. The Bill has effectively amended four sections of the Copyright Act, namely sections 22, 28, 33 and 46. A copy of the Bill is available here.

The Bill’s Memorandum of Objects and Reasons explains that the Copyright Act has been amended to “empower the competent authority to grant a compulsory licence for the publication or republication or broadcasting of works which are subject to copyright where it considers that the right holder withholds consent unreasonably. It [The Bill] also restricts the imposition of a tariff or levying of royalties unless approved by the Cabinet Secretary.”

It is recalled that four other sections in the Copyright Act were amended in 2012 in the exact same manner. Please see this blogger’s comments on the 2012 amendments here. What follows are this blogger’s thoughts on the 2014 amendments to the Act:

Section 22(5)

This is an amendment by insertion. The new subsection inserted relates to the principle of automatic protection under the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (Paris Text 1971). Article 5(2) of the Berne Convention reads:

“The enjoyment and the exercise of these rights shall not be subject to any formality; such enjoyment and such exercise shall be independent of the existence of protection in the country of origin of the work. Consequently, apart from the provisions of this Convention, the extent of protection, as well as the means of redress afforded to the author to protect his rights, shall be governed exclusively by the laws of the country where protection is claimed.”

This blogger reckons that this amendment is aimed at counteracting the effects of section 36 of the Act which requires authentication of copyright works.

Section 28(5)

The amendment to Section 28(5) states that the blank tape levy shall be collected by KECOBO and then distributed to “the respective copyright collecting society registered under section 46”. This wording is problematic since no CMO has been registered to administer audio blank tape compensation from the private copying of musical works and sound recordings.

Currently section 28(3) as read with section 30(6) of the Act provide that that owner of the sound recording and the owner of a related right in the fixation of a performance shall have the right to receive fair compensation consisting of a royalty levied on audio recording equipment or audio blank tape suitable for record and other media intended for recording, payable at the point of first sale in Kenya by the manufacturer or importer of such equipment or media.

Section 28(4) as read with section 30(7) further provides that the royalty payable under the above subsection (3) shall be agreed between organisations representative of producers of sound recordings, performers, manufacturers and importers of audio recording equipment, audio blank tape and media intended for recording or failing such agreement by the competent authority appointed under section 48.

From the aforegoing, it is clear that the copyright owners of musical works have been systematically side-lined from receiving any compensation from the collection of audio blank tape levies within the Republic of Kenya.

With reference to international best practices, it is clear that Kenya’s current legislative provisions on private copy levying are not only illegal but more importantly unconstitutional. This line of argument has been explored by this blogger here.

Finally, this blogger wonders whether the reference to “the respective copyright collecting society registered under section 46” in the amendment creates an opportunity for establishing a Collective Agency for blank tape levy administration. In other jurisdictions, such Agencies do exist and are made up of all CMOs that represent concerned rights holders.

Section 33A

This is an amendment by insertion. The new section inserted officially introduces compulsory licensing in Kenyan copyright law. However this blogger has argued previously that section 30A in the 2012 Amendments was the Government’s successful move to unofficially introduce a compulsory licensing regime under the guise of the right to equitable remuneration.

Compulsory license is the term generally applied to a statutorily license to do an act covered by an exclusive right, without the prior authority of the right owner. This concept of compulsory licensing in copyright is derived from patent law, where the owner is forced to face the competition in market, similarly in copyright law; the copyright holder is subjected to equitable remuneration. One of the main reasons for introducing non-voluntary licenses is where the users of certain works have access to these works on terms which are known in advance and it is not practicable for them to locate right owners and obtain an individual license from them.

Article 9(2) of the Berne Convention provides the legal basis for compulsory licensing in copyright law. The Article reads:

“It shall be a matter for legislation in the countries of the union to permit the reproduction of such works in special cases, provided that such reproduction does not conflict with the normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author.”

This provision provides the Convention’s exclusive basis for compulsory licensing and provides for the conditions which should be met before a member country can entirely excuse a use which includes compulsory licensing and not prejudicing the reasonable interests of the author. Therefore this Article provides the so-called three (3) step test for compulsory licensing, namely exceptional circumstances, no conflict with the normal exploitation of the work and no unreasonable prejudice to legitimate interests of the author.

Article 11 bis (2) provides that:-

“It shall be a matter for legislation in the country of the Union to determine the conditions under which the rights mentioned in the preceding paragraph [11 bis (1)] may be exercised but these conditions shall apply only in the countries where they have been prescribed. They shall not in any circumstances be prejudicial to the moral rights of the author, nor to is right to obtain equitable remuneration which in the absence of agreement, shall be fixed by competent authority.”

The amendment to section 33 emphasises the regulatory role of the Competent Authority (aka Copyright Tribunal) in compulsory licensing. This role is common in other common law jurisdictions such as the UK, US, Australia and India.

As this blogger has previously noted here, the reality in Kenya is that the Competent Authority provided under section 48 of the Act remains non-existent over a decade since the establishment of the Kenya Copyright Board (KECOBO). This situation is problematic as there are no mechanisms in place to monitor the practical implementation of the compulsory licences under section 30A and the proposed section 33A.

Section 46A

This is an amendment by insertion. The newly introduced section 46A creates an approval system for all tariffs set by CMOs to license copyright users. This new section prohibits any registered CMOs from imposing or collecting royalty based on tariffs that have not been approved and published in the Government Gazette from time to time by “the Cabinet Secretary in charge of copyright issues”. In addition, the new section empowers “the Cabinet Secretary” to exempt users of copyright works from paying royalties by notice in the Gazette.

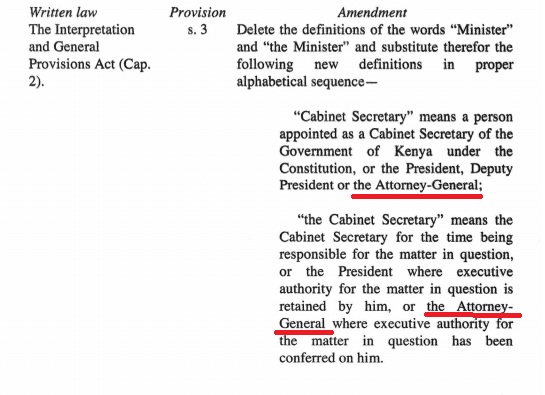

A preliminary issue that may require clarification is whether the Attorney General can be deemed to be “the Cabinet Secretary” for purposes of the Act? The Act defines “Minister” as “the Minister for the time being responsible for matters relating to copyright and related rights”. In the previous dispensation, the Attorney General (who was an ex-officio member of the Cabinet) assumed the role as “Minister” since KECOBO was under the Office of the Attorney-General. It is submitted that there is an established practice in Kenya whereby the Attorney General exercised the powers and performed the functions conferred on the “Minister” such as appointment of the Competent Authority and making Regulations for the better carrying out of the provisions of the Act.

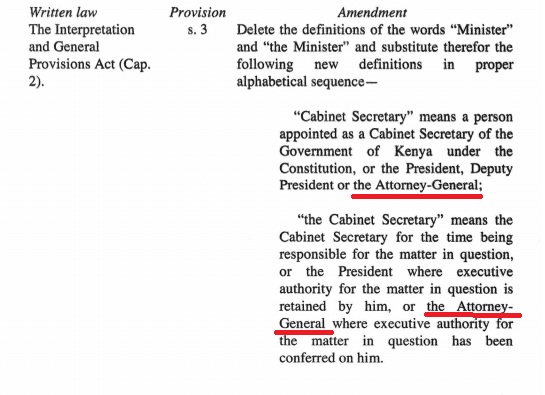

However this issue is now settled under the Statute Law (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act, 2014 which has amended the definition of “Minister” under the Interpretation and General Provisions Act (Cap 2 Laws of Kenya) making specific reference to the Attorney General. The relevant portion of the amendment has been reproduced below:

Nevertheless, this blogger maintains that the section 46A amendment may serve to further frustrate the relationship between CMOs and users of copyright. Over the years, this relationship has been severely strained due to the absence of the Competent Authority – a body which is authorised under the Act to deal with all issues relating to the licensing terms and conditions imposed on users by CMOs. The powers given to the Attorney General to approve tariffs and to exempt users from paying royalties may also prove problematic for CMOs.

Regrettably, this blogger notes that KECOBO and the Office of the Attorney General did not formally invite for public comments and/or conduct stakeholder consultations before causing these amendments to the Copyright Act to be passed by the Legislature and the Executive.

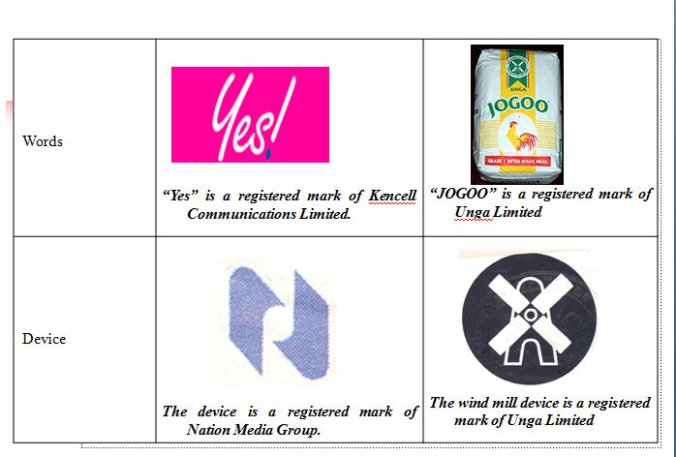

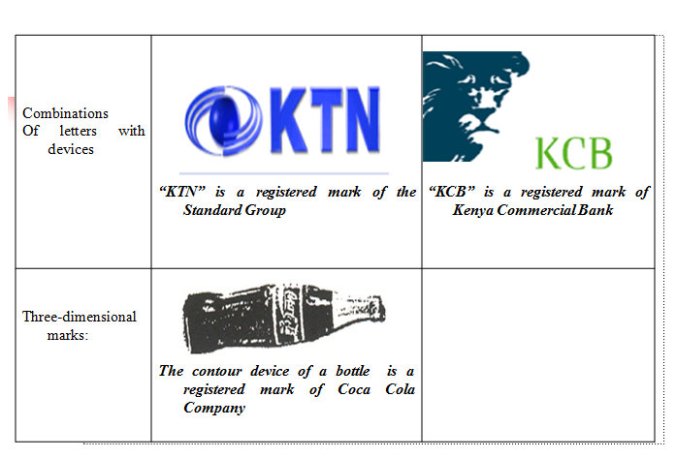

In the next blogpost, this blogger will discuss another set of IP law-related amendments with respect to the Kenya Anti-Counterfeit Act as contained in the Statute Law Miscellaneous Amendments Bill, 2014.