It is said that if you see a woman wearing the shoes pictured above, three things can be deduced. One, she spent an arm and a leg (and a foot?) on them. Two, those shoes are pronounced Christian Louboutin. Three, the surrounding women are a tad jealous.

This blogger has been following the spirited campaign by Christian Louboutin to assert and protect its trademark red sole, culminating in the highly anticipated outcome of its on-going court battle with fashion house Yves Saint Laurent (YSL).

The story goes something like this: in 1992, Christian Louboutin decided to give his shoes a distinctive feature by painting their soles with red nail polish. Over time, this red colour has become the signature look of his shoe collections. In 2008, the USPTO granted Christian Louboutin a trademark registration for the red-coloured sole in the following terms:

Trademark Reg. No:

3,361,597

Date:

January 1, 2008

Goods:

Women’s high fashion designer footwear

Description:

The color red is claimed as a feature of the mark. The mark consists of a lacquered red sole on footwear. The dotted lines are not part of the mark but are intended to only show placement of the mark.

In 2011, YSL came out with a collection of shoes that had varying colored shoes: purple shoes with purple soles, green shoes with green soles, navy shoes with navy soles and red shoes with red soles. Louboutin immediately moved to court to seek an injunction to prevent YSL from using the red sole, which the former alleged was trademark infringement in addition to a claim of $1 Million in damages.

The presiding District Court Judge Victor Marrero rejected Louboutin’s claims. His reasoning can be found at pages 21-22 and 29 of the judgment:

“Louboutin’s claim to “the color red” is, without some limitation, overly broad and inconsistent with the scheme of trademark registration established by the Lanham Act. Awarding one participant in the designer shoe market a monopoly on the color red would impermissibly hinder competition among other participants…”

(…)

“the Court cannot conceive that the Lanham Act could serve as the source of the broad spectrum of absurdities that would follow recognition of a trademark for the use of a single color for fashion items. Because the Court has serious doubts that Louboutin possesses a protectable mark, the Court finds that Louboutin cannot establish a likelihood that it will succeed on its claims for trademark infringement and unfair competition under the Lanham Act. Thus there is no warrant to grant injunctive relief on those claims.”

This decision was not received well by many who argued that the iconic red soles were not merely decorative but in fact fulfill a very important trade mark function insofar as they indicated the origin of Louboutin’s shoes and distinguished them from other women’s shoes.

The matter went on appeal and was decided by appellate court justices José Cabranes, Chester Straub, and Debra Livingston. This court has reversed the earlier decision and stated the following in its recent judgment:

“We hold that the District Court’s conclusion that a single color can never serve as a trademark in the fashion industry was based on an incorrect understanding of the doctrine of aesthetic functionality and was therefore error […]We hold that the lacquered red outsole, as applied to a shoe with an ‘upper’ of a different color, has ‘come to identify and distinguish’ the Louboutin brand […] and is therefore a distinctive symbol that qualifies for trademark protection.”

Although the Appeals Court ruled that Louboutin’s trade mark had acquired a ‘secondary meaning in the public eye’, it instructed the USPTO to limit Louboutin’s red sole trade mark to uses which the red sole contrasted with the remainder of the shoe:

“We conclude, based upon the record before us, that Louboutin has not established secondary meaning in an application of a red sole to a red shoe, but only where the red sole contrasts with the “upper” of the shoe. The use of a red lacquer on the outsole of a red shoe of the same color is not a use of the Red Sole Mark.”

Given the territoriality of IP, the question remains: would a colour trademark be registrable under Kenyan law?

Comments:

It is arguable whether the Registrar of Trademarks at Kenya’s Industrial Property Institute (KIPI) as well as the courts would allow attempts to “monopolise colour”. The question of colour trademarks arose partially in the Court of Appeal case of British American Tobacco v Cut Tobacco Kenya Ltd (2002) where it was said:

“[I]t has to be observed that the use of the colour red as the predominant colour on a packet of cigarettes is not the exclusive preserve of anybody, including the plaintiff, the colour being a conventional indicator in the tobacco industry of a strong brand of cigarettes.”

However it is clear that in the above case, the colour red had not acquired a secondary meaning in the context of cigarettes. In fact, the court of appeal was guided by evidence that in tobacco industry both in Kenya and internationally various colours are used to denote different brands, for instance variations of colour red denotes strong cigarettes, variations of colour blue denotes mild/light cigarettes; and variations of colour green denotes menthol cigarettes.

Nevertheless, it remains debatable whether Kenyan law allows for trademark registration of colour per se or colour that has acquired a secondary meaning associated with goods or services.

It is clear from the Trademarks Act no 4 of 2002 is that colour may be a factor when considering the distinctive character of a mark. section 19(1) of the Trademarks Act no 4 of 2002 makes the following provision:

“A trade mark may be limited in whole or in part to one or more specified colours, and in any such case the fact that it is so limited shall be taken into consideration by the court or the Registrar having to decide on the distinctive character of the trade mark.”

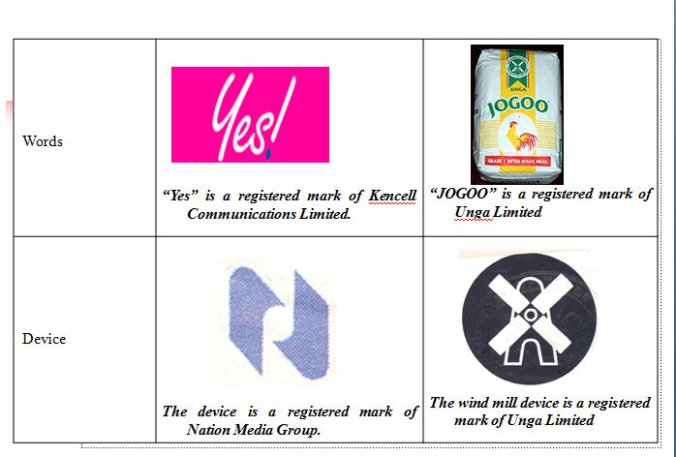

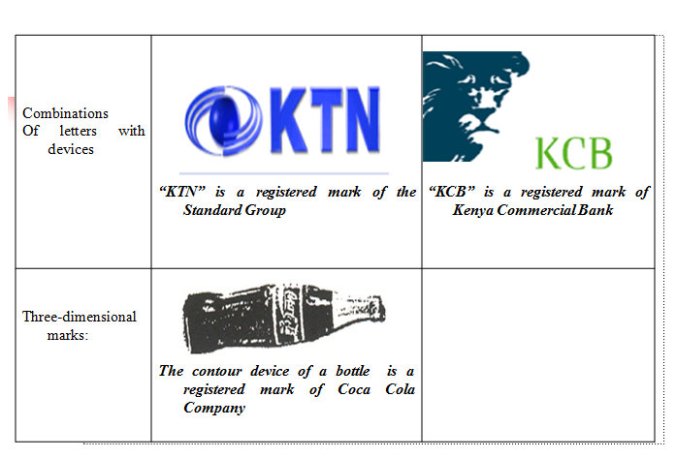

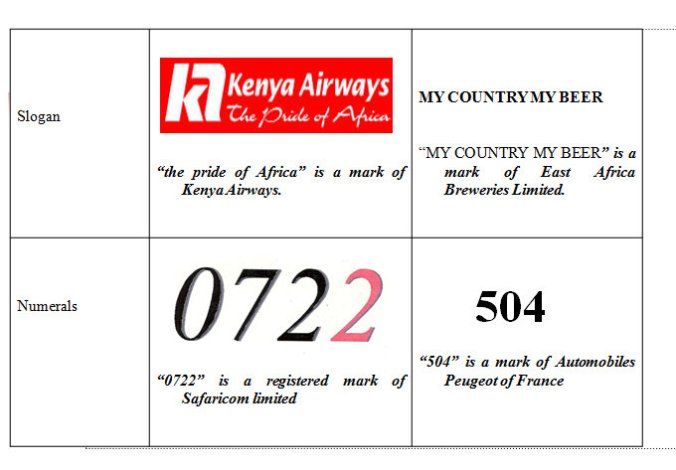

However the current Act fails to expressly cite ‘colour’ in the list of signs that are considered to be “marks”. The Act defines “marks” as follows:

“mark” includes a distinguishing guise, slogan, device, brand, heading, label, ticket, name, signature, word, letter or numeral or any combination thereof whether rendered in two-dimensional or three-dimensional form

However it is argued that a purposive and contextual interpretation of the word “includes” in this section of the Act would indicate that the list above is not exhaustive. Thus, there is no reason why distinctive colours should not be registered as trade marks. In future, a great test case might arise if a new Telcom company decided to enter the market using the Green colour associated with Safaricom in their branding. Assuming Safaricom hasn’t already trademarked their color in the area of telecommunications services, perhaps Safaricom has acquired a common law trademark in their colour?