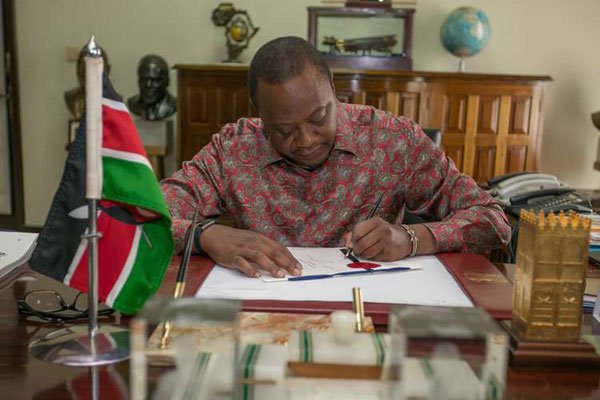

On 31 August 2016, President Uhuru Kenyatta (pictured above) assented to the Protection of Traditional Knowledge and Cultural Expressions Bill, No.48 of 2015. The Bill was published in Kenya Gazette Supplement No. 154 on 7 September 2016 cited as the Protection of Traditional Knowledge and Cultural Expressions Act, No. 33 of 2016. The date of commencement of the Act is 21 September 2016, which means the Act is now in force. A copy of the Act is available here.

In previous blogposts here, we have tracked the development of this law aimed at creating an appropriate sui-generis mechanism for the protection of traditional knowledge (TK) and cultural expressions (CEs) which gives effect to Articles 11, 40 and 69(1) (c) of the Constitution. This blogpost provides an overview of the Act with special focus on the issues of concern raised previously with regard to the earlier Bill.

The Preamble of the Act is brief and simply states that this Act provides “a framework for the protection and promotion of TK and CEs”. However as shall be revealed from the analysis below, the Act is disproportionately protectionist with little or no provisions on support, access, development, let alone promotion of TK and CEs.

Section 2, which is the Interpretation section, is at the core of the challenges facing the operationalisation and implementation of the Act. Despite our previous concerns with regard to key definitions in earlier versions of the draft Bill, this section in the Act remains problematic in at least three key respects.

Firstly, the term “Cabinet Secretary” is ambiguously defined as the “Cabinet Secretary responsible for matters relating to intellectual property rights”. This definition effectively renders the Act legislatively orphaned since it has no clear parent Ministry responsible for oversight, administration and enforcement. To be sure, this definition may be interpreted to cover at least four different Ministries namely the Office of the Attorney General, Industrialisation, Sports, Arts and Culture or Agriculture. Out of these four potential Ministries, the Office of the Attorney General might seem to be the most likely Ministry in charge of the Act since Kenya Copyright Board (KECOBO), a state organ under the Attorney General’s Office, has been designated under the Act as host institution for the Traditional Knowledge Digital Repository (TKDR) as well as an arbiter for settlement of concurrent claims to TK by different communities. Secondly, the definitions of “owner” and “holder” are defined in almost identical fashion with the definition of “owner” overlapping with that of “community”. There is also reference to the synonymous term “custodian” in the body of the Act which is not defined in this section. Finally, the term “exploitation” is defined pejoratively with the inclusion of expressions like “selfish purposes” and “taking advantage of unwary holders” yet in the body of the Act, the term is used in neutral terms in the context of authorisations, licenses and assignments granted to users.

Sections 4 and 5 are commendable as they seek to entrench the constitutional principle of devolution into the Act. However as alluded to above, there is no clarity on which ministry or agency will be responsible for the Act at the national level whereas at the county level, the Act is clear that the county executive committee member responsible for matters relating to culture within the county government shall be responsible for the Act. In addition section 5 calls for several amendments to be effected to the Copyright Act relating to the functions of KECOBO vis-a-vis the establishment and maintenance of the TKDR.

Section 7 remains problematic since in the event of concurrent claims by communities, it is not clear whether KECOBO or the concerned county government(s) will have the primary role of resolving such disputes. This is as a result of an overlap of responsibilities between both levels of governments with regard to maintaining the Repository. In this regard, it is submitted that section 22 ought to have been amended to require that the register of licenses/assignments be kept by KECOBO since the latter is in charge of the TK Repository at the national level. In this regard, it is submitted the power to settle disputes about ownership of rights in section 30 of the Act would be better placed in the hands of a tribunal to be established under the Copyright Act. Finally, it is unclear whether the references to “the Authority” in sections 32 and 42 refer to KECOBO or some other state organ.

It may have been instructive for the Act in section 8 to borrow a leaf from the provisions of the Industrial Property Act and Trade Marks Act with respect to the establishment and maintenance of the county registers and TKDR generally. A great deal of information appears to be missing regarding formalities for application, processing and registration of TK and CEs at county and national levels. In this regard, it is further submitted that this section may consider introducing a system of inspection of the TKDR for purposes of searches to be conducted by prospective users as well as the introduction of a TKDR Journal (akin to the Industrial Property Journal) for notifications, advertisements and any other relevant publications related to administration of the Act.

The compulsory license regime under section 12 of the Act is problematic largely due to the inclusion of the term “prior informed consent”. It is clear that if there is compulsory licensing then there can be no prior informed consent. In other words, the compulsory acquisition of TK or CEs presupposes that consent has been withheld by the community/owner. Furthermore the dispute resolution provisions in subsections (2) and (3) create two parallel avenues through the courts and the Cabinet Secretary since it is clear that “a dispute” in subsection (3) may relate to a determination of “compensation” in subsection (2).

There is need to harmonise section 18 of the Act with the existing provisions of the Copyright Act relating to folklore. In those provisions, the Attorney General is granted certain express powers with respect to authorising and prescribing the terms and conditions governing any specified use of folkore or the importation of any work made abroad which embodies folklore.

While it is acknowledged that the Act defines derivative works as works derived from TK or CEs, its application in section 20 is problematic since such works are relevant in copyright but have no legal meaning for purposes of industrial property such as trade marks, patents and industrial designs. Similarly, the Act in section 22 problematically borrows the intellectual property law framework of licensing and assignment of rights yet in the context of TK and CEs, the concept of assignment would be contrary to the very nature of the rights in TK and CEs held by a community.

Sections 24 to 36 of the Act contains useful provisions relating to management of rights in TK and CEs which cannot be operationalised without clarity on who exactly is the Cabinet Secretary and/or national agency responsible for the Act.

Finally, section 37 to 41 deal with sanctions and remedies under the Act. It is observed that the offences and penalties provided in section 37(1),(2),(9) and (10) are problematic due to their punitive nature since they apply indiscriminately to both third parties as well as bona fide members of a community.