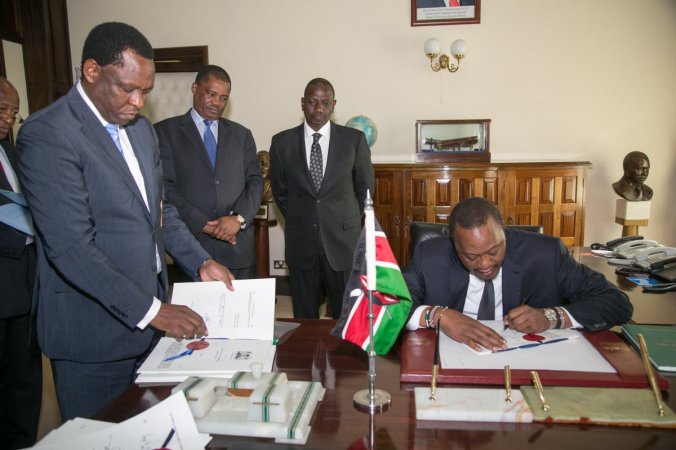

On 16 May 2018, President Uhuru Kenyatta (pictured above) assented to the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Bill, 2018. The Bill was passed by the National Assembly on 26 April 2018. Readers of this blog will note that, unlike the previous Computer and Cybercrimes Bill, 2017 that was first tabled in Parliament, the Act now contains some new provisions relating to blockchain, mobile money, offences related to cybersquatting, electronic messages, revenge porn, identity theft and impersonation, as well as the newly created National Computer and Cybercrimes Coordination Committee. A copy of the Act is available here.

From an intellectual property (IP) perspective, the Act is significant for several reasons, including that it creates new offences and prescribes penalties related to cyber-infringements, it regulates jurisdiction, as well as the powers to investigate search and gain access to or seize items in relation to cybercrimes. It also regulates aspects of electronic evidence, relative to cybercrimes as well as aspects of international cooperation in respect to investigations of cybercrimes. Finally it creates several stringent obligations and requirements for service providers.

In section 2 of the Act, cybersquatting is defined as: ‘the acquisition of a domain name over the internet in bad faith to profit, mislead, destroy reputation, or deprive another from registering the same, if the domain name is – (a) similar, identical or confusingly similar to an existing trademark registered with the appropriate government agency at the time of registration; (b) identical or in any way similar with the name of a person other than the registrant, in case of a personal name; or (c) acquired without right or IP interests in it.’

In section 28, the offence of cybersquatting reads as follows: ‘A person who, intentionally takes or makes use of a name, business name, trademark, domain name or other word or phrase registered, owned or in use by another person on the internet or any other computer network, without authority or right, commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding two hundred thousand shillings or imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years or both.’

These provisions on cybersquatting may become problematic in cases where the registrant registers a domain name incorporating a well-known mark without the proprietor’s permission for purposes of expressing criticism or appreciation (‘gripe’ or ‘fan’ sites). Apart from opportunistic cybersquatting or cyber-griping, genuine disputes may also arise where the same mark is used by different persons in respect of different goods and services. For example, where two companies have independent, legitimate rights to a name, such as an American company that sells software under the name ‘Java’, and a Kenyan company that sells food and beverages under the name ‘Java’.

Similar to cybersquatting, there is the ambiguous offence of identity theft and impersonation in section 29 which states that: ‘A person who fraudulently or dishonestly makes use of the electronic signature, password or any other unique identification feature of any other person commits an offence and is liable, on conviction, to a fine not exceeding two hundred thousand shillings or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or both.’ The term ‘unique identification feature’ is not defined in the Act but it may be interpreted to include social media accounts and profiles or other types of online persona relating to individuals or businesses.

Another important aspect of the Act is on the liability of online service providers. In the Act, ‘service provider’ is defined as ‘a public or private entity that provides to users of its services the means to communicate by use of a computer system; and any other entity that processes or stores computer data on behalf of that entity or its users.’ Further, section 56 appears to create a new safe harbour for service providers. It states that:

‘A service provider shall not be subject to any civil or criminal liability, unless it is established that the service provider had actual notice, actual knowledge, or willful and malicious intent, and not merely through omission or failure to act, had thereby facilitated, aided or abetted the use by any person of any computer system controlled or managed by a service provider in connection with a contravention of this Act or any other written law.’

Similarly, with regard to the anti-circumvention principles of the WIPO Internet Treaties, the Act now provides an extra layer of protection in addition to the Copyright Act. Sections 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 of the Act construct a new list of cyber-offences relating to unauthorised access, access with intent to commit further offence, unauthorised interference, unauthorised interception and illegal devices and access codes, respectively. At their core, these sections function for IP owners as anti-circumvention prohibitions. These prohibitions cover the manufacture or possession of an anti-circumvention device or the use of such a device to circumvent security measures. However it is clear that these prohibitions are not copyright-specific but apply to all data.

On child pornography, section 24(1)(c) curiously states as follows:

’24.(1) A person who, intentionally — (c) downloads, distributes, transmits, disseminates, circulates, delivers, exhibits, lends for gain, exchanges, barters, sells or offers for sale, lets on hire or offers to let on hire, offers in another way, or make available in any way from a telecommunications apparatus pornography, commits an offence and is liable, on conviction, to a fine not exceeding twenty million or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding twenty five years, or both.’

The above provision appears to criminalise ALL copyright works defined under the Act as ‘pornography’ whereas the stated purpose of the Act is to address specifically the prohibition of ‘child pornography’.

On computer fraud, section 26 of the Act appears to add an additional avenue for criminal enforcement action for authors and owners of certain computer-based literary works. This provision uses words like ‘alteration’, ‘modification’ and ‘copying’ in the context of compilations of data and computer programs, which are already categorised as works protected under copyright law.

The offence commonly referred to as ‘revenge porn’ is criminalised in section 37 of the Act titled ‘wrongful distribution of obscene or intimate images.’ The section states that: ‘A person who transfers, publishes, or disseminates, including making a digital depiction available for distribution or downloading through a telecommunications network or though any other means of transferring data to a computer, the intimate or obscene image of another person commits an offence and is liable, on conviction to a fine not exceeding two hundred thousand shillings or imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years or both.’ From a copyright perspective, this section appears to curtail the exclusive rights of authors and owners in their works. As highlighted by this blogger in a post here, it is important that revenge porn provisions emphasise that the sharing in question must be done primarily with the purpose of causing embarrassment or distress.

On the Act’s investigation procedures, it is noted generally that the enforcement provisions in the Act appear to presume that accused persons may not have any protected IP assets of their own such as copyright works, patents, trademarks, designs among others stored on their computer systems. Thus the Act appears to sanction illegal appropriation of proprietary information through mass collection of IP contrary to the Constitution.

A longstanding question in online IP enforcement is electronic evidence, as detecting and proving infringement is often a challenge. In this regard, section 47(2) of the Act states that: ‘In any proceedings related to any offence, under any law of Kenya, the fact that evidence has been generated, transmitted or seized from, or identified in a search of a computer system, shall not of itself prevent that evidence from being presented, relied upon or admitted.’ However, there are a couple of remaining challenges, including difficulty linking virtual identity to real-world people and associating online data to physical locations. These problems continue to challenge evidence used in online IP infringement cases.